Date01.03.16

AuthorDr. Raed Samra

CompanyDar Al-Handasah

LocationKingdom of Saudi Arabia Middle East

The ongoing expansion of the Holy Haram is a tale of bold minds and devoted efforts.

In Makkah, a new sanctuary is emerging.

Grand in appearance, vast in volume, meticulous in detail, the expansion project of Makkah Haram is steadily materializing, much to the appreciation of pilgrims.

Hailed as the biggest project in Islam’s history, it will significantly facilitate the journey of millions of the faithful to Holy Makkah.

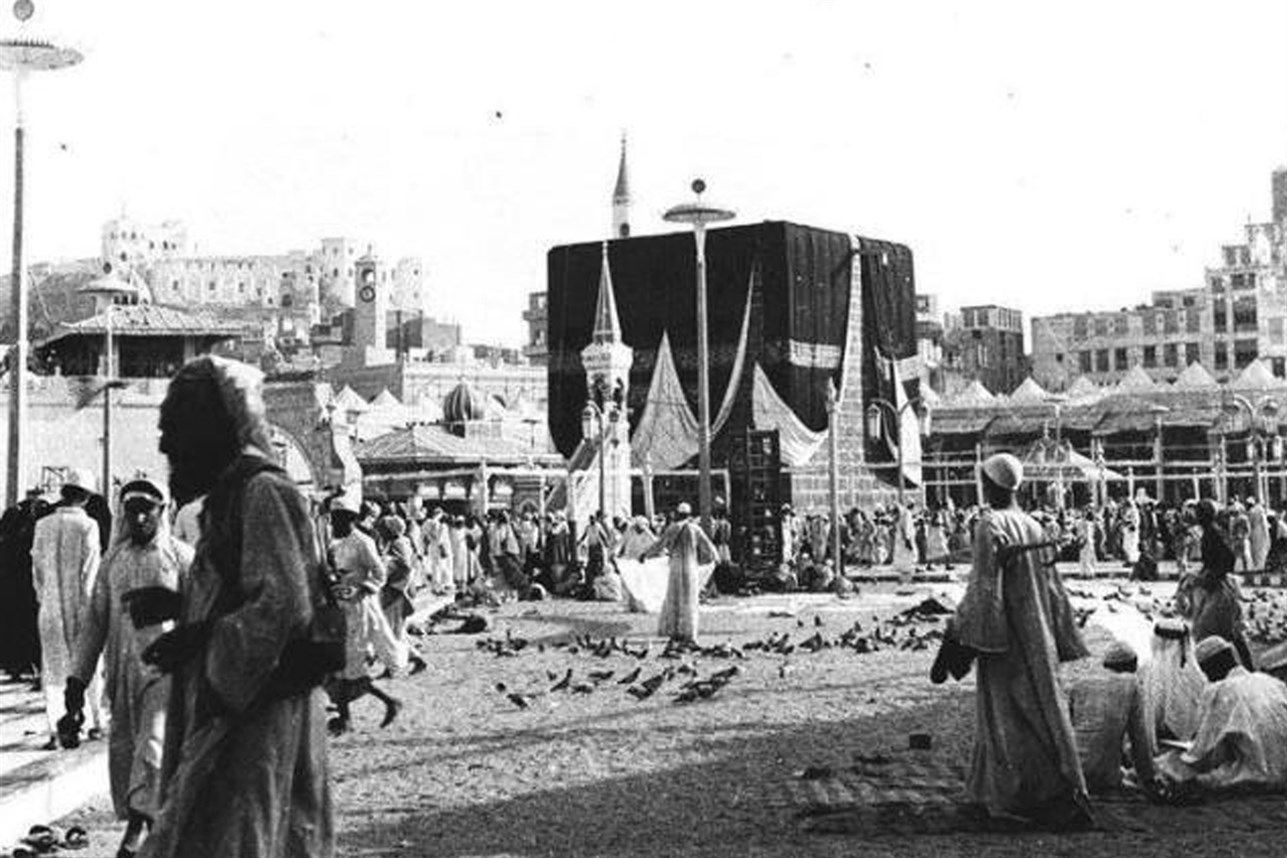

The Haram before expansion

Centuries of piecemeal intensifications of Makkah, linked to the city’s demographic evolution, progressively enclosed the heart of Masjid Al-Haram, Al-Ka’bah, depriving it of visibility and restricting expandability. Cloth merchants, spice traders and other businesses were parked right outside the Haram. A solution was needed to restore Masjid Al-Haram’s central position in the City, and give the mosque an architectural and engineering dimension able to welcome the growing number of pilgrims in an atmosphere of safety and religious practice.

The expansion

Thus came about the Haram expansion project, which aims to provide new praying areas and essential services to millions of pilgrims who visit Makkah seasonally for Hajj and Umrah. With Al-Ka’bah as its pivot, the project extends radially outwards across a distance of 684 m. It includes the construction of a new Haram building, courtyards around the mosque, a new services building, a Central Utility Complex (CUC), a hospital, civil defense and security facilities, as well as bridges and pedestrian walkways.

Scale, to many observers, is perhaps the Haram expansion’s most impressive feature. Extending along the northern front of the old Haram, the project covers 1,500,000 m2, of which 1,100,000 m2 is built-up area. Such a scale allows the new Haram to welcome about one million pilgrims simultaneously, exceeding the current capacity even when all expansions are taken into account.

The expansion paves the way for several beautiful additions. Four tall minarets surpassing 100 m

and two monumental ones surpassing 400 m will be built. In addition, there will be several sliding domes ranging in size from 16 to 36 m and 29-m movable skylights.

From day one of the design process, the team’s premise was: “Quality is not something that just happens. It is rather a result of genuine intellectual effort.” For them, quality translated into sustainable design, resilience, longevity, high standards and specifications, and the choice of strong materials.

Accessibility

One of the first design considerations was accessibility. Ease of access is crucial for such a populated space, and a complex series of structures links the sites and allows fluid mass movement. Four bridges connect the new Haram building to the old Haram; four bridges connect the services building to the new Haram building; and one bridge connects the services building to the Masa’a. Access among the various Haram areas and levels, service buildings and piazza is made possible by staircases, elevators and more than 500 escalators, capable of 22 hours of operation a day.

To facilitate the flow of the pilgrims in and out of the Haram, four pedestrian tunnels totaling 4,200 m in length connect the services building to Al-Hojoun and Jarwal districts. The pedestrian tunnels are cross-linked with two emergency tunnels.

Crowd management happens on an incredible scale as the pilgrims who flock to Makkah number in millions. At Haram entrances, cameras count occupancy and monitor crowd movement. New technologies allow the use of accurate models, and when coupled with a deep understanding of crowd psychology, identify densities, risks, delays, actions, and reactions that large groups of people can generate.

Crowd movement in the Haram expansion is assisted by wayfinding features. These use architectural clues, lighting, sight lines, and signage to give the users strong indicators of where they are and how to get to their destination from their present location. In addition to being guides, the signs serve as integrated ornaments.

Entrances, another extremely important component, are accounted for by two main gates and eleven minor gates. Furthermore, there are two helipads at the services building, and one helipad at the hospital and security buildings located at Al-Hojoun.

A utility tunnel serves as the main artery, harboring utilities from the CUC to the Haram, including chilled water, water supply, firefighting, waste water, refuse collection, and electric cables.

Water needs

Water is the lifeblood of the pilgrims’ journey. That is why water proofing and other measures were employed to ensure that the spring water, Zamzam, remains contaminant-free. A chilled water plant at the CUC has 24 chillers with a daily capacity of 120,000 t of chilled water conveyed via four 1,200 mm pipes. One 1,400 mm pipe serves the Haram water supply requirements, and two 400 mm lines serve the internal and external firefighting networks, with all required pumping units. Eight chillers can be added to increase the capacity by an additional 40,000 t. Two more generators can be added to the standby generators plant. A special Automated Waste Collection System (AWCS) has the capacity to remove 600 t of waste daily. The gray water treatment plant can produce 14,000 m3/day using biological treatment, chlorination and filtration, and dispense of it through irrigation.

Resilience

For resilience, the team forecast environmental conditions to the severest levels for a 100-year period, and the design integrated the findings. Structurally, earthquake loads and extreme temperature effects were also factored in. For the columns and walls, high-strength concrete in excess of 75 MPa was produced, with actual test results showing records above a robust 100 MPa. Stainless steel was used abundantly to counteract a lingering enemy, rust, and proved to be a cost-effective, low-maintenance solution.

Resilient concrete posed special challenges. This was due to the Arabian environment, which is awash with hot and dry weather. Other challenges arose due to time-consuming concrete overhauls from ready-mix plants and a frequent use of 200-m long casting lines on-site. Micro silica and fly ash were used as cement replacement in concrete.

The micro silica and fly ash served as plasticizer and helped reduce the energy expended and carbon dioxide levels produced by cement manufacturing. To bring this benefit to perspective, it is worth knowing that the project requires about three million m3 of concrete.

Behind the scenes: Waste, emergencies and power backup

The AWCS employs suction to move the waste from the storage sections in the Haram building to the collection terminal at CUC, some 1,100 m away. A refuse cyclone separator separates the air and the waste bags. The waste is then compacted and locked under negative pressure in a fully sealed container, ready to be transported away.

Several devices are in place for emergencies. Two types of sprinklers aid in firefighting, operating as a wet system and a water mist system. Fire extinguishers use an ozone friendly gaseous suppression agent. For smoke evacuation, fire zoning is employed and smoke curtains are positioned every 60 m along the main corridor. For safety and security, access control is provided for doors at important building rooms, offices and electromechanical areas. An automated operation system is provided to monitor and control MV switchgears network using Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems. Backup is provided to ensure continuous, uninterrupted performance of all systems. In the event of power shutdown, uninterruptible power supply (UPS) can provide 30% of the lighting power and 100% of the power for safety, security and communication loads. Ease of expandability is central in design, along with flexibility and individuality.

Special challenges

Challenges were part and parcel of the Makkah Haram project. In addition to durability and scale, there were challenges due to the social and religious nature of the project.

One of the greatest challenges was the condition imposed by the client for uninterrupted visitor traffic. Despite it being a fast-track, design-build project, construction still had to protect the constant flow of pilgrims at all times. To meet this requirement, a strenuous work schedule of 20-hour work days and 120-hour weeks was enforced.

On-site engineers also had to accommodate city regulations requiring closures of the main roads two to three times daily at peak hours, which slowed down materials’ delivery to the site. Rock excavation ‑all 13.2 million m3 of them‑ had to be completed while employing controlled blasting and complying with strict noise and vibration limits. And, because of their immediate proximity to the existing Haram, materials and vehicles required careful maneuvering.

Since water is the lifeblood of the pilgrims’ journey, water-proofing measures ensure that the spring water, Zamzam, remains contaminant-free.

Throughout the project, rigorous measures of quality were applied. Some are evident, but most are invisible. For example, durability considerations prohibited the use of paint. Instead, white, red and blue aggregates are used to give a permanent, maintenance-free, colorized effect. Structural performance was inspected. Strain gauges are embedded in some rafts to measure deformations.

Thermocouples were installed in massive columns to measure differential temperature between the core and outside surfaces.

The new Haram is a gigantic work of art and engineering. Walking down the ceremonial zone, the spine of the Haram building, one is easily overtaken by the grandiosity of the monument. The great volume, vast height and lofty, spaced columns amplify the beauty and provide a direct line of sight to the Ka’bah ‑Islam’s sacred shrine. High-quality decorative marble, a colossal central dome and calligraphy of inscribed verses from the Quran further permeate calm and spirituality.

For Dar’s dedicated design and supervision teams, the Haram expansion demanded an extremely high level of coordinated and enduring effort. The phrase “work ethic” took on new meanings, becoming a way of achieving the team’s mission in this historic project.