A movement for the planet

It is now more than 30 years since the World Commission on Environment and Development issued the seminal Brundtland Report, “Our Common Future,” drawing the world’s attention to the concept of sustainable development, outlining guiding principles, and promoting economic and social advancement in ways that avoid environmental degradation. In the words of the Norwegian politician Gro Harlem Brundtland, sustainable development was defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” So how far have we come since 1987?

Two years after the Brundtland Report was published, the Earth Summit was held in Rio de Janeiro, and the global sustainability agenda began to evolve. In September 2000, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were introduced: eight goals mainly targeted at the developing world and with a specific focus on education, gender equality, poverty and hunger, child mortality, maternal health, HIV/AIDS and other diseases, the environment, and global partnerships.

By the target deadline of 2015, these goals had registered both successes and failures. As then UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon stated, the MDGs helped lift more than one billion people out of extreme poverty, made inroads against hunger, enabled more girls to attend school, and helped protect the planet. But as he also went on to state, inequalities persisted, progress was uneven, and around 1.5 billion people in conflict‑affected countries and on society’s margins were unreached.

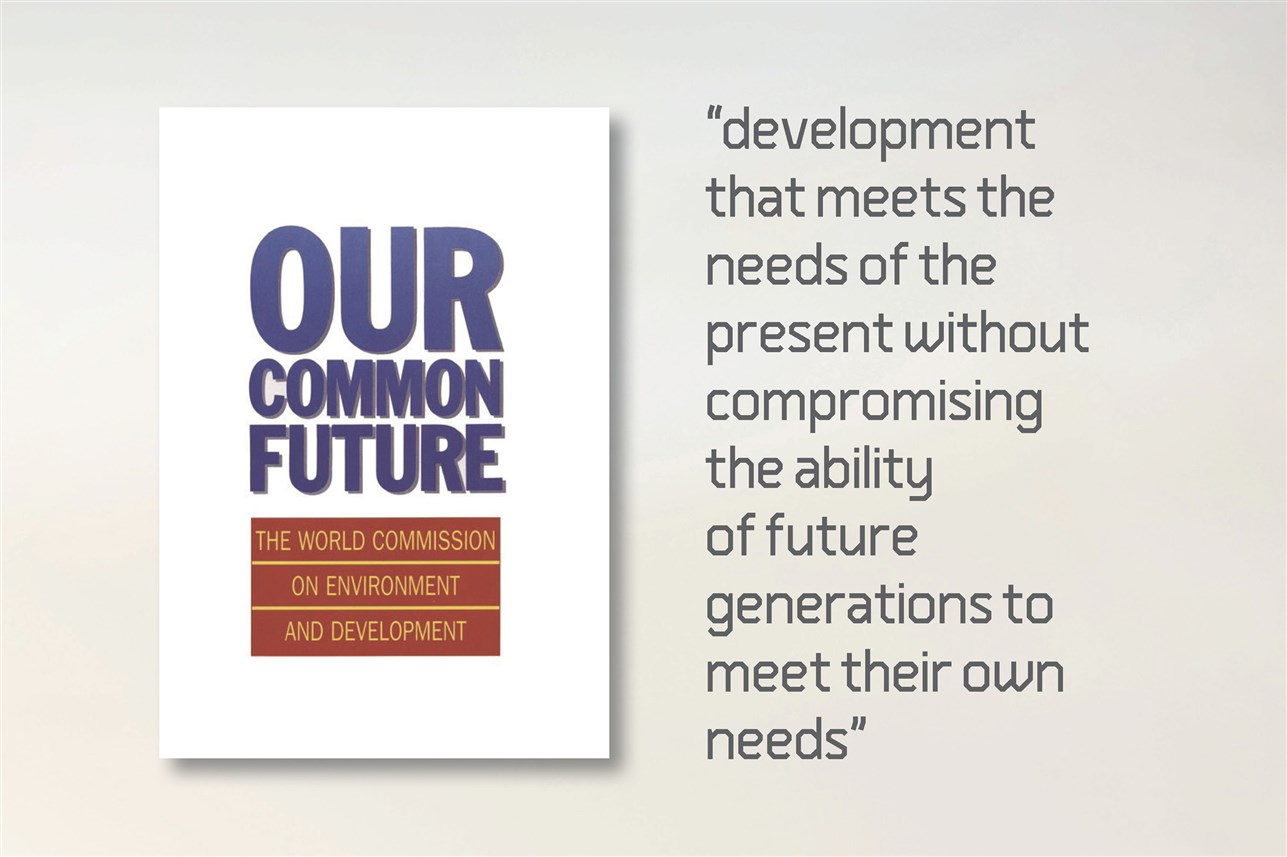

When the MDGs expired in 2015, it was determined that an all-encompassing sustainability agenda was required for the developing and developed worlds alike, where environmental sustainability, social inclusion, and economic development should be equally valued. The baton was passed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): seventeen goals that provide a detailed, comprehensive, and holistic approach to sustainable development.

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The headings listed above are only a guide to contents, and each SDG is broken down into numerous targets and indicators. These goals do not apply only to the developing world: in fact, the SDGs are unique in that they call for action by all countries – poor, rich, and middle-income alike – to promote prosperity while protecting the planet. Moreover, they recognise that ending poverty must go hand-in-hand with strategies that build economic growth and address a range of social needs including education, health, social protection, and job opportunities all while tackling climate change and environmental protection.

These goals currently mark the pinnacle reached by the global community. Yet, 2019 began with a show of impatience from the United Nations. The Secretary General, António Guterres, regretted the lack of transformative changes since the seventeen SDGs were adopted by world leaders in September 2015, and he called for acceleration, stating that member states should have a “sharper focus on…delivering strong and inclusive economies while safeguarding the environment.”

Dar signs global commitment to sustainability

Within the context of this critical global movement, Dar chose to become a signatory to the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) and a member of the UN Global Compact Network Lebanon (GCNL). The UNGC is the world’s largest corporate sustainability initiative and a call to companies everywhere to align their strategies and operations with universal principles of human rights, environment, and anti-corruption. One of the objectives of this initiative is to drive business awareness and action in support of achieving the SDGs by 2030. Dar’s decision to sign this compact is a natural outcome of the company’s commitment to corporate responsibility, but it throws down a challenge to every individual in the group: how do we show leadership in implementing the SDGs?

Championing Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

In Lebanon, Dar Chairman and CEO Mr. Talal Shair joined the SDG council of the GCNL and is serving as the Goal Leader for ‘SDG 16 – Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions.’ The council’s mandate is to use its members’ private sector leadership to support and guide the GCNL in its efforts to make progress towards the SDGs, whether through advancing policy dialogue, advocacy, and lobbying or through promoting relevant research and related projects.

As such, Dar now has a formal role in leading the promotion of Goal 16 in Lebanon. The goal acknowledges that peaceful and inclusive societies, in which individual rights are protected, are essential to sustainable development. While Dar has no direct role in preventing violence, sexual abuse, and human trafficking, our work can support some of the objectives for this goal. We can stand against corruption and bribery; we can design effective, accountable, and transparent institutions; we can specify responsive, inclusive, participatory, and representative decision-making at all levels; and we can support non-discriminatory laws and policies that promote sustainable development.

Frontiers moving forward

Yet, Dar’s commitment to supporting the SDGs was never meant to be limited to one goal or one country. Drilling down on just one SDG’s set of detailed objectives raises a question: how many of the seventeen SDGs are relevant to the company and the many disciplines it accommodates? It is hard to imagine many organisations with such broad activities that they will be able to make a difference on all. There’s no doubt that Dar has a role to play in creating ‘Sustainable Cities and Communities’ (Goal 11) and in forming ‘Partnerships for the Goals’ (Goal 17), but how much impact can we have – as individual, specialist consultants or in the way we run our own company – over the full list of goals?

What we find as we become familiar with the detailed list is that we touch on many of these areas in our working lives and, whether we have ‘environmentalist’ in our job titles or feel a personal attachment to these goals, we have a corporate mission as employees of Dar to contribute to the sustainability of the physical, biological, social, and economic world. It will be in our clients’ interests too, as it becomes more common to score funding bids by compliance with the SDGs.

Where might the SDGs come into play? There are some obvious areas. Marine dredging impacts ‘Life below Water’ (Goal 14). Water infrastructure projects obviously contribute to ‘Clean Water and Sanitation’ (Goal 6) while waste management infrastructure ought to contribute to ‘Responsible Consumption and Production’ (Goal 12). Equally, the goal of ‘Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions’ (Goal 16) is furthered by the institutional assessments that form part of some spatial strategies. Still we must be careful about congratulating ourselves for superficial links. It is how we all do our work – whether as engineers, designers, planners, or project managers – that makes a real contribution to these goals.

SDGs in action: the case of the Ibadan City Master Plan

Awarded the first prize in the “International Award for Planning Excellence” category during the 2019 Royal Town Planning Institute Awards for Planning Excellence, Dar’s city master plan for Ibadan in Nigeria shows how projects can apply the detail and spirit of the SDGs during development. The master plan’s Strategic Environmental and Social Assessment (SESA) used the SDGs as a framework to guide the development of objectives and indicators against which the evolving master plan could be reviewed, to ensure a sustainable Ibadan society covering environment, vulnerable groups, and economy. The SESA objectives provided a set of clear statements that embodied the identified environmental and social concerns relating to implementation and assisted in comparison of alternative master plan scenarios.

Although not all SDGs were relevant to the master plan design (ending the poaching of protected species, a Goal 15 target, for example), reviewing development of the master plan against the framework of the SDG/SESA objectives, the urban design team and the client could be confident that a broad-ranging sustainability standard had been employed as a benchmark.

Moreover, as part of capacity building training in 2016 for the Ibadan City Master Plan and the Epe Master Plan, both in Nigeria, the SDGs were introduced to client teams during workshops, as frameworks for the development of sustainable societies. Workshop activities included encouraging participants to use the SDGs to develop SMART objectives, targets, and indicators relating to their specific project locations. The strength of these master plans in the areas of stakeholder engagement and preservation of cultural heritage and archaeology can be attributed in part to the SDGs, and capacity building itself is recognised as contributing to ‘Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions.’

Measuring progress

How is sustainability advancement being measured? For certain, the UN is not waiting until 2030 to determine whether the goals have been met. Instead, it established the High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF), a forum that meets annually and plays a central role in the follow-up and review of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the SDGs at the global level. The HLPF meeting, this July in New York was designed to carry out reviews of the Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) submitted, at the time of this writing, by around 50 developed and developing countries. The VNRs are voluntary and state-led, involving ministerial and other high-level participants, and they are important in providing a platform for partnerships. After Lebanon submitted its first VNR in 2018 , those of us based in London were interested this year to see the United Kingdom’s first VNR of its own progress in meeting the SDGs, which was published on the 14th of June.

The UN’s July 2019 Forum, in addition to reviewing submitted VNRs, has a particular focus on progress with SDGs 4, 8, 10, 13, 16, and 17.

“Sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony, but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, and the orientation of technological development and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs.”

A process of change

In Gro Brundtland’s words, “sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony, but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, and the orientation of technological development and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs.” Sustainable development is indeed a process of change, but the clock is ticking, and none of us has any time to waste.